08 August 2025

Esra Özdoğan

To Elif

Old Loyalties

The short list of words that one feels one must resort to, but I will nevertheless try to refrain from using: Multifaceted, of a diverse spectrum, a Renaissance man, polymath, homo universalis… What exactly is it that we find disturbing in these attributions? That they are shorthand definitions, divisive in their scope while encompassing through diminution? Is it the paradox of the “jack of all trades”, a much more general view that broad knowledge is not possible even in a single field? Or that they emphasize the medium, the materials, the tool-kit rather than the human being? Is it the thought or suspicion that, if he were alive today, Samih Rifat himself would oppose such attributions, and treat these received labels as pejoratives? More or less, all of the above. But the greater reason is that, in today’s perception, being capable of multiple tasks, displaying multiple fields of interests or possessing multiple virtues, risks rendering invisible a strong singular identity and its vertical ramifications. Multiple directions refer not to a sense of direction, but dispersion. They correspond to the horizontal liberty of different hats worn for different circumstances, to uncertainty, and to a fragmented, flexible, free-floating and unorthodox pluralization. Such a postmodern identity may be desirable for many. However, the Samih Rifat I remember had built the paradigm of all the work he achieved with a modernist ethic and attitude. He would prefer definite, accurate, unapologetic, universal, integrative and perhaps absolute truth to ambiguous, fragmented and relative realities. This was an ethical stance concerned that realities numbering as many as there are intellects and identities (or hats), would shift the legitimate ground of aesthetics and knowledge, and lead to negative outcomes such as the loss of virtues. Therefore, it seems more accurate to claim that Samih Rifat, with his different fields of occupation, gathered rather than divided himself and used these fields as integrative tools without compromising the aesthetic direction and harmony he had in mind. To prioritize the dialectics between a subject and his objects and then to read this fundamental relationship not through identities and hats, but via media that shape and enrich the same body could be a more loyal and accurate approach.

Loyalty is important, because it is the key concept when we think of Samih Rifat; and because it involves the vertical connections he inherited, swore to protect until the end, and structured his consistent and singular identity around. He was a person who had taken over a modern repertoire of images that operate with consistent connections, and he was determined to not only remain loyal to this heritage until the end, but also to enrich it, to open different doors around it and to let new shoots burgeon. Someone who thought with root images, someone who looked out for them with every tool he had inherited to use, inside language, among languages, in the construction of the visual, in the representation of the structure, and after poetry, by lifting barriers, and who had spread his wings for this paradigm.

A root image in the universe, for instance “stone”. When I look back today, I realize that from this stone that reveals nothing to eyes devoid of curiosity, from only one of the holy relics in his possession, Samih Rifat devised a map of belonging and loyalty. In the hermetic words of Heraclitus, for instance, the stone is in transformation like everything else in the world, it rises up against its apparent deceptive nature and flows, it does not stop, it becomes one of the first appearances of dialectics; and in another aspect in Heraclitus, stones becomes pawns, game stones in the hands of life depicted in this instance as a child[1]. In another journey, in Paul the Silentiary’s Hagia Sophia, the stone preserves its purest existence and multiplies; inscribing the nature of the land of Atrax, Proconnesus Mountain, Lydia and the hills of Galia on the enlightened face of civilization. The stone in Hagia Sophia, the splendid design of the diversity of earth, comes from where it belongs, from great ravines and fertile planes to display its nature in all its purity in a manmade building. “...that of glittering black upon which the Celtic crags, deep in ice, have poured here and there an abundance of milk,”[2] transforming architecture into the veritable negative of a photograph. In Leonardo’s riddles the stone is brought out from the depths of caves, becomes an object of desire for human beings and their wars, because now it emerges as the most valuable metal, “it is for the stone that countless creatures die, and the trees of broad forests are destroyed.”[3] Stones now in the hands of humans become one of many dark semblances of civilization. Following a long journey, it is again the same stone that becomes the heavy mass of sealed words in René Char, a distant relative of Heraclitus. Melih Cevdet adds the stone into the alchemy of aged words, “the stone, next thing you know, turns into gold,” he says, leading towards a mysterious path full of surprises. Oktay Rifat rests his back, along with Agamemnon, on the stones of certain ages; in another poem, he once again places the same stones right opposite mortals, Stones, he says, “are in close embrace with immortal Gods.”[4] The body of Abidin Dino on his deathbed turns into a stone statue, his “hand taking flight”[5] failing to stand up. Samih Rifat continues to have stones read in myriad languages. He reads Seferis’s stones, the stones that served as home to death, to the grave, to birds, and to Anatolia, miracle of civilization, in the cave churches of Cappadocia first in his own language in translation, and then in a more universal language, with the writing of light, in his photographs, over and over again.[6] Stones traverse Samih Rifat’s photographs from one end to the other, they become sculptures, faces, bodies, structures. He now seeks to solve the cipher and promise of mass, not with his words but with shadow and light, with texture, contrast, with positive and negative space, with his eyes. Through his lens, an old marble inscription inSabahattin Eyüboğlu’s garden is frozen once again with its weight; this time, the relationship of stone with words, with both human beings is written by the silent language of photography. The stone keeps transforming, stiffens, crumbles, flutters, liquefies, changes colours, yet never ends. In Ada/Island, that pure text that even in its own crystal lucency inevitably meets with the image of the stone, speaking of the sea, shore, fish, and several other root images, Samih Rifat manages to skip a stone in between: “A detail: workers who process marble go blind at a young age, having constantly looked at the sun, and at white surfaces.” [7]

Truths and Virtues

Even this poorly tracked family tree of a randomly picked single image, even this road map Samih Rifat draws with his mother tongue, metalanguage, hand, eye and passionate sympathies, does in fact display how modernist understanding holds a central place in his paradigm. These categorical images that stand behind the tools, never disperse, and withdraw and gather themselves just when they appear to be scattered away, with their diverse manifestations embrace nature and a progressive and humanistic understanding of the world in the form of a system. For Samih Rifat, the ambiguous is acceptable only within a poem, and even there, if the power of allegory and association does not impose its own normative structure in language and form, if it is not promoted by masterful technique, it melts away. In the Preface he wrote for his translation of Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece, too, he mentions the invariable principle of art, and potential absolutes: “Nevertheless, certain issues he discusses, and especially his observations on description, the relationship of form/content, the share of spirituality and thought in art contain deep truths, questions and answers that are valid for all ages –and perhaps all branches of art.”[8]

In his documentary Simurg, he reaches the artists he refers to as the thirty birds after absolute truth, the “deep facts” he mentioned above with the voice of Attar, who said, “You are truth, and no one else”. The fact that the only novel with three translators into Turkish is titled The Quest of the Absolute [La Recherche de l’absolu], and that the Turkish text of this work by Balzac features the signatures of Sabiha Rifat, Oktay Rifat and Samih Rifat is surely no coincidence in this context. Three translators who believe in the continuity of ideal representations for an interrupted single narrative, in different periods, perhaps by correcting each other, lend a voice to an author they believe in: “A mosaic tells the tale of a society, as the skeleton of an ichthyosaurus opens up a creative epoch. All things are linked together, and all are therefore deducible. Causes suggest effects, effects lead back to causes. Science resuscitates even the warts of the past ages.”[9]

“All are deducible...” says Balzac’s voice from the pen of three translators.

“All things are one thing, one thing is all things,” says Oktay Rifat in a distant poem.

“When you kiss a stone, light sheds its silent weight” writes Samih Rifat in his notebook, perhaps in a draft for a poem. Perhaps, by kissing that piece of mosaic, he wanted to trigger, once again, that ancient chain of belonging, and under its guidance, reach the enlightenment of truth, and perhaps the absolute, who knows.

In brief, it is certain that the aesthetic principle, the standards of which were determined from ancient idealism on, and formed by related voices that responded to each other from myriad different times and by the search for knowledge, for Samih Rifat, came together in the idea of truth, in both senses of the word. And also, that he shaped his stance that opened no doors to coincidence in literature, art or thought, his methodical industriousness, and his principled, uncompromising stance. It is meaningful from this viewpoint that both of his translation from Plato are Socratic dialogues, and besides, that they are dialogues that focus on duty, virtue and loyalty (truth, again, and absolute value). In Crito, Socrates’s voice invites his student to the pleasure of methodical knowledge: “See, then, that the starting point of the inquiry is laid down to your satisfaction and try to answer the questions in the way you think best.”[10] In Apology, the same voice argues that even his own children should be put on trial if they stray from principle, virtue and responsibility: “then reprove them, ..., for not caring about that for which they ought to care, and thinking that they are something when they are really nothing.”[11] In the pursuit of the absolute which excludes haphazardry, waywardness and swaying from the path, Samih Rifat selected the books he would translate from among those texts where he could combine his voice with that of the author.

All these examples show the idea or belief of how, in his world of meaning, the Author, or in its general sense, the auteur, has not died. Samih Rifat does not believe in a writer who both withdraws and is held back from a postmodern perspective. The creator, for him, is not a centerless, fragmented figure. His position is not variable. The author has not withdrawn from the text; his strength has not been broken. He is always concerned about adding more integrity to his work. He pays heed to causal relationships and aims for consistency. The author is not a stack of discourses that possesses the function of writing, but a single and masterful narrator who is determined to sustain the tradition operating as Socratic dialogue. He does not abandon his guidance of the reader, he does not allow for great diversions, he continues to join the reader. The fact that Samih Rifat began almost every single text he translated into Turkish with a preface he personally penned is proof of that. As he, on the one hand, acts as guide for the reader, on the other hand, in these prefaces which announce himself, his language and his loyalties, we observe, first and foremost, that Cartesian resistance that rejects the destruction and undermining of the subject. The creator, for Samih Rifat, is a “master” at the most modest level, as for its language and discourse, it is a family identity. To hold back the creative subject, to miss its unique language is no different to him than losing a family.

Photograph: Between Hunters and Gatherers

As such, it will be more meaningful, in discussing Samih Rifat’s relationship with photography, to mention another means of expression that connects to the integral structure he built rather than remembering Samih Rifat the photographer and talking about another hat he wore. To read his photographs by isolating them from his writings on photography, his poetic language and poetry criticism, his translations and architectural endeavours and his method of thinking would mean leaving his perspective regarding the visual image stunted.

In his book titled Akla Kara Arası/Between Black and White which compiled his writings on photography, he mentions a shadow he always envied as a photographer. One may at first think that the shadow envied by the photographer could be the shadow inside another photograph. Or, that it is a shadow in the external world, within the day and reality, a shadow that at a certain hour falls on the opposite side of the lightened face, which the eye of the lens never succeeded in matching its beauty in reality. Yet the shadow, the image of which Samih Rifat envies, in a manner which is in fact not surprising at all, comes from within words, and in fact, from within words he himself translated into Turkish. This is the dark silhouette of the guard in Ritsos’s poem, Evening; “His shadow stretches out across the plane like Agamemnon’s corpse, huge.”[12] Agamemnon, again, this time burdening the guard wandering around the remains of past time with his own history.

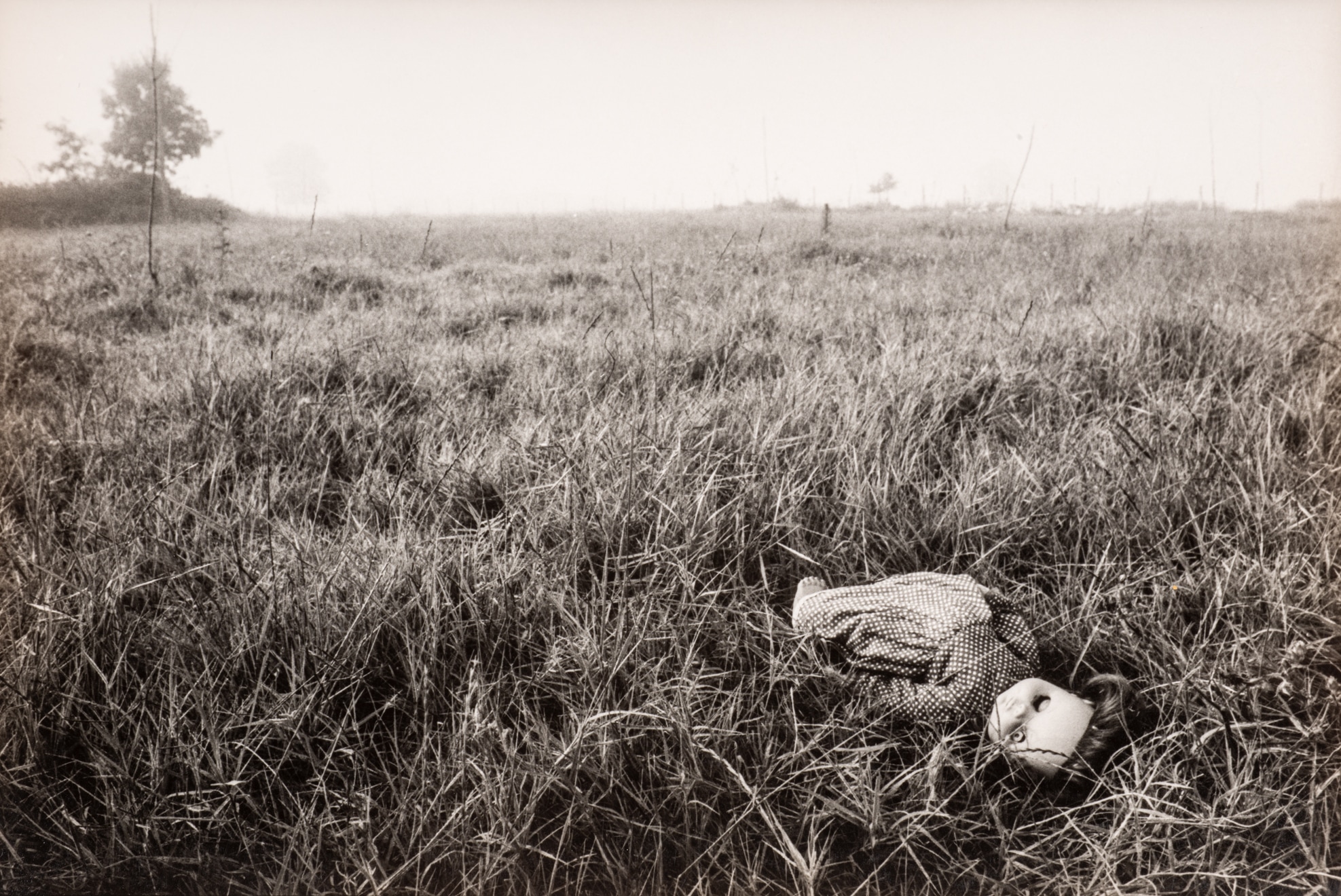

Is it then possible to envy words for a photograph? Can a literary shadow, transmitted from one language to another, then, with a completely different rhetorical packaging, be translated once again with the fragmentary language of the visual image? Like words flowing in time, can poetry reach its semantic capacity in photography, an image frozen in time? Or, from an inverted viewpoint, could it be possible to create a poem in the geometry and space of the image, could it be possible to render legible, not a shadow at degree zero, but a shadow that has also shouldered the dead body of Agamemnon? Samih Rifat’s relationship with photography stands, in the fullest sense, on the line where opposing responses to these questions intersect, on the threshold that separates these responses. Even though it has long been accepted and become widespread today for contemporary photographers to produce conceptual art objects, build narratives and form visual poetry, this is still a threshold that defines the distinction between photographers, theorists or photography lovers who treat photography as the identical copy of reality and those who argue that this object can be read as a unique mimetic creation on the plane of idea and creation. Samih Rifat stands precisely at that threshold, and on one side of this threshold (and in my opinion, on the inside, the closed side) stands the modernist, black-and-white, Magnumist photography tradition which perceives photography as a certificate of reality, with its idea of success locked in on the percentage of truth it contains, the aesthetic pleasure its reference provides, and the purely geometric translation of external reality. This is the field of photographers who, in the framework of ethical values determined by the post-war humanistic European Left, established their practices on exact definitions and unswerving conduct, and continue their search for a humane world on the principle of pinning down photography within an identity of accurate documentation and true evidence. This is the school of normative photographers, which I personally find too masculine, which rejects definitions such as artist, poet or creator, and has persistently resisted the reading of the lyricism reflected in their photographs or the plastic foundations of the images they captured within the scope of art. “Grand masters” like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ara Güler and Josef Koudelka, of whom Samih Rifat always speaks with great respect, admiration and excitement in his photography criticism, whom he always followed in his own photographs and perhaps most emulated, hold a huge place on this side of the threshold. As for the other side of the threshold (outside, perhaps in the garden, in open space) we find Şahin Kaygun, whom Samih Rifat always referred to as “my lost friend” and saw as a competent creator in the “systematic excavation and research of the boundless means of expression the phenomenon of photography holds beyond the direct process of shooting and printing”[13]. And there we also find Yıldız Moran, a woman photographer, who established her discourse in this medium on the idea of “poetry”, whose work was overlooked until recently, yet in 1998, Samih Rifat remembered her in his article titled A Story of Forgetting and Being Forgotten[14]. There is Eugène Atget and his “manic passion”, a photographer from a much older era, who did not even feel the need to position himself, and in Samih Rifat’s words, “a man who approached the image before him with the passion of a prophet, a seer, a poet or a lover”[15]. In other words, active or passive creators who intuitively questioned the potential openings of photography on the level of discourse or production, and at times in a formal sense, and who instead of hunting, capturing images, gathered the different possibilities of expression in the garden of photography, stand on this side of the threshold.

Photographer as Flâneur and Poet

As for the threshold, there we find a Samih Rifat who reserved a distinct place to the camera among all the media he used, and often spoke of how he drew great pleasure and joie de vivre from taking photographs. When he talked about his own photographic production, he said that he perceived photography not as an art but a ‘craft’, but he also strove to bring the shadow of poetry into photography. He likes to think of himself as a ‘colleague’ of the marketplace photographer, street photographer, wedding photographer or local photojournalist in a small town, but he writes, “I have always thought that the art form closest to photography is not painting as it is widely thought, but writing, or rather, poetry”[16]. In consideration of his thoughts on photography’s forms of existence, this is because he is also aware of the complexity and ambiguity of labels and definitions that perhaps stem from the nature of this field of occupation. Within this ambiguity, he claims that a viewer may not be able to distinguish between Henri Cartier-Bresson and an average photojournalist, and think that they do the same job. One could say that both in his photographs and in his metalanguage on photography he tries to overcome this ambiguity to some extent. When we look at the modest borders he draws for his own photography, one could falsely think that Samih Rifat produces, structures and imagines photography as document. If his ideas and writings on photography are not taken into account, his works, too, mostly support this impression. His work includes portraits, self-portraits and family portraits shot for magazines, and the exterior and interior space details of protected areas and architectural structures, and the rugged surfaces of monuments and stones, suitably shaped by light, also feature dominantly in his photographs. In these works, which includes slide films, black-and-white negatives and polaroids, streets, urban topography and historical remains shot during photographic journeys hold a significant place. In his images that are close to the modernist photographic tradition, we often meet compositions of geometric forms, and textures shaped by light.

However, when talking about the work of photographers he met with great excitement, travelled with and at times, had the joy of working together, he goes beyond the modest boundaries he draws for his own photographs. He always tried to summon Ara Güler, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Koudelka to the place they always denied themselves, to drag them onto the other side of the threshold. He finds Ara Güler to be too resistant and he tries to pull him at least onto the threshold, to his side: “From his photographs, you may think that you are in the presence of a pure poet, yet from his words that appear increasingly angry recently, you could think that he was a strict documentarist, who acts almost like an enemy of the concept of art. However, he stands between the two.”[17] In the same manner, when they look at a photograph by HCB with Koudelka, Samih Rifat reads “a kinship of literature and art” on appearance. Yet Koudelka tells him that “it is unnecessary for photography to convey such layers of meaning”[18]. Nevertheless, this persistent stance will not prevent him from referring to Koudelka’s camera as a “magician’s instrument”, and to read his photographs within the framework of lyricism.

From what I have learned from Samih Rifat, Robert Capa one day told Henri Cartier-Bresson, who was developing a fancy towards surrealism: “Shun labels. They give you confidence, but once you get labelled, you can never get rid of it. You will always remain a small surrealist photographer. (...) Continue along your path, but with the label ‘photojournaliste’, and hide the rest in the depths of your heart.”[19] Although HCB kept to this advice, Samih Rifat adorns him with the qualities of an artist, with those of an auteur in the full sense of the word: “In surrealism, HCB discovers a dream world, imagination, poetry, the importance of the subconscious as a unique source, social defiance, the miracles that coincidence can create, in brief, the definition of a new and free worldview, and a new form of existence.”[20]

At the threshold he blends the mind and the heart, the moment of decision becomes for him also an act of love. Geometry is both a sensation, and also one of the absolute laws, indispensable truths he always remained faithful to when it came to art. Yıldız Moran’s photography was for him, “first and foremost a story of passion”. This is why he does not forget Yıldız Moran, who three years after Roland Barthes described photography as an “uncoded message”[21] in 1980, displayed the courage to say, “photography has another aspect; its subjective aspect. That is what distinguishes a newspaper interview and a poet. You can use a pencil for many things, and the same goes for the camera,”[22] Samih Rifat remembers a woman photographer, who, like him, stood at the threshold, with the foresight of a clairvoyant:

“...when a “museum of photography” is founded in this country, when the values of the past are brought together with belated appreciation, Yıldız Moran will have a warm and exciting corner there, have no doubt about it!”[23]

In the same framework, he writes about how Atget’s “docile lunacy” and how he transforms the city streets in his images into a surrealistic world. When he speaks of the first photograph shot on earth, the garden photograph of Nicéphore Niepce, he claims that the photographer could see from that back window the path that only poets and children knew. This is perhaps why, when he describes Şahin Kaygun, remembering him with the idea of a journey to the borders of photography, he structures his metalanguage in the form of free verse:

“A good song is sung sometimes

looking at a wound,

at a happiness, at a love,

at fears, meanings, or the lack of meaning.

And the key in these lines

is the word inside, if you ask me.

Because the task of art, is the effort to create

by looking at things we have inside

rather than outside.”[24]

In this way, he places the photographer, the true hunter of images, the flâneur who does not only wander the city streets but also traverses the world and faraway lands, close to the poet, who looks inside himself and seeks purity. He always renders that shadow he envies available and possible for myriad photographers on both sides of the threshold.

To read Esra Özdoğan's full article, you can check out the exhibition catalogue. Click here for more information about the catalogue.

[1]Samih Rifat, Herakleitos, Bir Kapalı Söz Ustasıyla Buluşma Denemesi [Heraclitus, An Attempt to Meet with a Master of the Closed Word], Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul, November 2004, p.

[2] Mabeyinci Pavlos, Ayasofya’nın Betimi [Paul the Silentiary, A Description of Hagia Sophia], Translated into Turkish by Samih Rifat, İstanbul Araştırmaları Enstitüsü, Istanbul, April 2010.

[3]Leonardo da Vinci, Bilmeceler (Kehanetler) [Riddles], Translated into Turkish by Samih Rifat, Sel Yayıncılık, Geceyarısı Kitapları, Istanbul, March 2001, p. 31.

[4]Oktay Rifat, Bütün Şiirleri I [Complete Poems I], Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul, February 2014, p. 569.

[5]Jean Pierre-Deleage, Abidin Dino ya da Kanatlanan El [Abidin Dino or the Hand that Took Wings], Translated into Turkish by Samih Rifat, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul, January 2007.

[6]Yorgo Seferis, Kapadokya Kaya Kiliselerinde Üç Gün [Three Days at the Cappadocia Cave Churches], Translation and Photographs, Samih Rifat, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul, April 1997.

[7] Samih Rifat, Ada [Island], Sel Yayıncılık, Istanbul, 2002, p. 68.

[8] Honoré de Balzac, Gizli Başyapıt [The Unknown Masterpiece], Translated into Turkish by Samih Rifat, Can Yayınları, August 2015, p. 9.

[9] Honoré de Balzac, Mutlak Peşinde [The Quest of the Absolute], Translated into Turkish by Sabiha Rifat, Oktay Rifat, Samih Rifat, Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2007, p.

[10] Platon, Kriton ya da Görev Üstüne [Crito], Translated into Turkish by Samih Rifat, Can Yayınları, Istanbul, January 2023.

[11] Platon, Sokrates’in Savunması [Apology], Translated into Turkish by Samih Rifat, K Kitaplığı, Istanbul, 2002.

[12] Samih Rifat, Akla Kara Arası/Between Black and White, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul, September 2002, p. 31.

[13]Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 105.

[14] Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 59.

[15] Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 14.

[16] Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 37.

[17] Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 123.

[18] Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 21.

[19] HCB Fotoğrafçı [HCB Photographer], Pera Museum Catalogue, Edited by Samih Rifat, Istanbul, January 2006, p. 20.

[20] ibid. p. 20.

[21] Roland Barthes, La Chambre Claire, Cahiers du Cinéma. Gallimard - Seuil, Paris, 1980, s. 179. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, Reflections on Photography, Translated by Richard Howard, Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1981, p.

[22]Yıldız Moran, Interview in Ses Magazine, 25 June 1983. https://www.yildizmoran.com.tr/1983-06-25-yilldiz-moran-roportaj

[23]Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 59.

[24]Samih Rifat, 2002, p. 98.

Published as part of Pera Learning programs, “The Little Yellow Circle (Küçük Sarı Daire)” is a children’s book written by Tania Bahar and illustrated by Marina Rico, offering children and adults to a novel learning experience where they can share and discover together.

The New Year is more than just a date change on the calendar. It often marks a turning point where the weight of past experiences is felt or the uncertainty of the future is faced. This season, Pera Film highlights films that delve into themes of hope, regret, nostalgia, and new beginnings.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)