17 September 2019

Having penetrated the Balkans in the fourteenth century, conquered Constantinople in the fifteenth, and reached the gates of Vienna in the sixteenth, the Ottoman Empire long struck fear into European hearts. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, its expansion had stalled. With the waning of the so-called Türkengefahr (Turkish threat) and the rise of commercial trade facilitated by the nascent European empires, there was a major shift in the way the Ottomans were represented in European visual and literary culture. Over time, the Ottoman Empire came to be viewed not as an imminent threat but rather as an interesting —pardon the anachronism— tourist destination that could be visited and explored, and from where exotic goods could be purchased and taken home as mementos. During the eighteenth century, travel to the Orient became an opportunity for upper-class Europeans to further their education and broaden their culture, a phase in their coming of age; and oriental objects became prestige items and prized consumer goods. Turquerie (lit. “Turkish stuff”) is a cultural and artistic movement that emerged and developed in this context.

In fact goods produced in the Orient, such as Ottoman rugs and silk-velvet textiles, had been popular in Europe since earlier times. Indeed such items appear so frequently in Renaissance paintings that certain Anatolian carpets with geometric patterns are now known as “Holbein rugs” —because they often appear in the works of the German painter Hans Holbein the Younger (d. 1543)— while certain Aegean carpets with stylized floral designs are called “Lotto Rugs” —because they often appear in the works of the Italian painter Lorenzo Lotto (d. 1556). Ornaments inspired by Arabic script (but generally illegible) have appeared in European painting since the Middle Ages, and in the most unexpected places, notably the halos of the Christ and the Virgin Mary, and the borders of important clergymen’s vestments.

Still, some changes, both qualitative and quantitative, are in evidence from the eighteenth century on. Indeed, Turquerie is only one of several —distinct but related— currents that emerged during this period. Along with such trends as Orientalism, Exoticism, Chinoiserie (lit. “Chinese stuff”), Africanism, and Primitivism, Turquerie is just another aspect of European artists’ search for inspiration in cultures other than their own. It is well known that Mozart (d. 1791) drew inspiration from Turkish music in the eighteenth century, Degas (d. 1917) and van Gogh (d. 1890) from Japanese woodcuts and Gauguin (d. 1903) from Polynesian carvings in the nineteenth, and Picasso (d. 1973) from African sculpture, Pound (d. 1972) from Chinese and Japanese poetry, and Stravinsky (d. 1971) from Russian pagan music in the twentieth. Moreover these trends were not limited to “great” artists: from household furniture to wallpaper, from glassware to clothing, and from architecture to theater, Europe “consumed” the world during this period not only politically and economically but culturally as well. To properly appreciate the movement known as Turquerie, it is necessary to bear in mind this historical context.

In its first recorded use, to describe the miser Harpagon in the comedy L’Avare (1668) by Molière (d. 1673), the term “turquerie” meant “hard-heartedness” or “cruelty”: “What’s more he is Turkish,” Molière wrote, “but of a turquerie to make everyone despair.” After the 1669 visit of the Ottoman ambassador Müteferrika Süleyman Ağa to the French court under King Louis XIV (d. 1715), however, the term became more benign and, with the staging of Molière’s Le Bourgeois gentilhomme the following year, quite facetious: representing the aristocratic oxymoron “bourgeois gentleman,” the protagonist Monsieur Jourdain was made a fool of by his daughter’s young suitor Cléonte who put on Turkish garb and passed himself off as the Turkish sultan’s son. As a result of the play’s popularity, Turkish (or pseudo-Turkish) attire and Turkish (or pseudo-Turkish) themed costume balls became quite trendy. Through this new fashion, the fascinating unknowability of the Orient was to a degree domesticated, while, on the other hand, it became possible for European authors to criticize the social and political problems in their own societies by projecting them onto the oriental Other.

Still, as Alexander Bevilacqua and Helen Pfeifer put it, Turquerie “was not solely a European representation of a foreign people, but a set of responses to an increase in the movement of Ottoman goods and ideas. The trajectories by which everything from coffee and costumes to music and manuscripts travelled from Ottoman to European lands suggest that Turquerie was a dynamic and multi-actor phenomenon in which Ottomans played a key role. Ottoman objects did not travel naked: they were wrapped in layers of meaning.” (“Turquerie: Culture in Motion, 1650–1750,” Past & Present 221 [2013], pp. 75–76.)

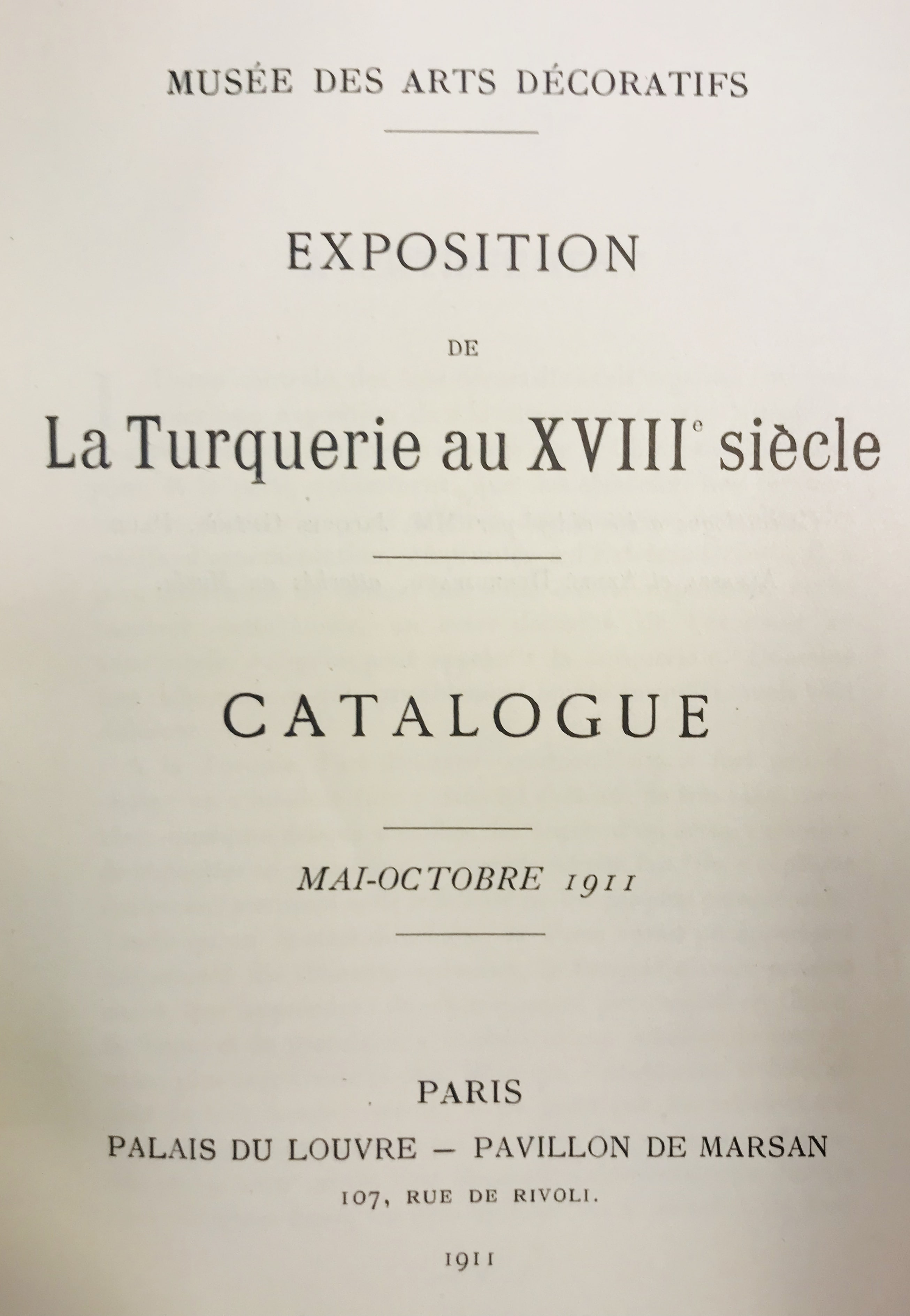

In time, Turquerie became an aesthetic term for an à la mode oriental theme or inspiration in art, literature, architecture, furnishings, fashion, masquerade culture, and even cuisine. Yet, when the Central Union of Decorative Arts (L’Union centrale des arts décoratifs) organised an exhibition of eighteenth-century Turquerie in 1911 in Paris, the art critic and curator Paul Alfassa concluded that the Ottoman influence on the decorative arts had been negligible in comparison to that of China, and that “it is almost uniquely in painting that we must search for a ‘Turkish’ influence.” (Exposition de la Turquerie au XVIIIe siècle [1911] p. 5–6) While this assessment is somewhat exaggerated, as noted by Nebahat Avcıoğlu and Finbarr Barry Flood, “the circulation of images was integral” to the burgeoning cultural exchange between “Orient” and “Occident” that began in earnest in the eighteenth century. (“Globalizing Cultures: Art and Mobility in the Eighteenth Century,” Ars Orientalis 39 [2010], p. 31.)

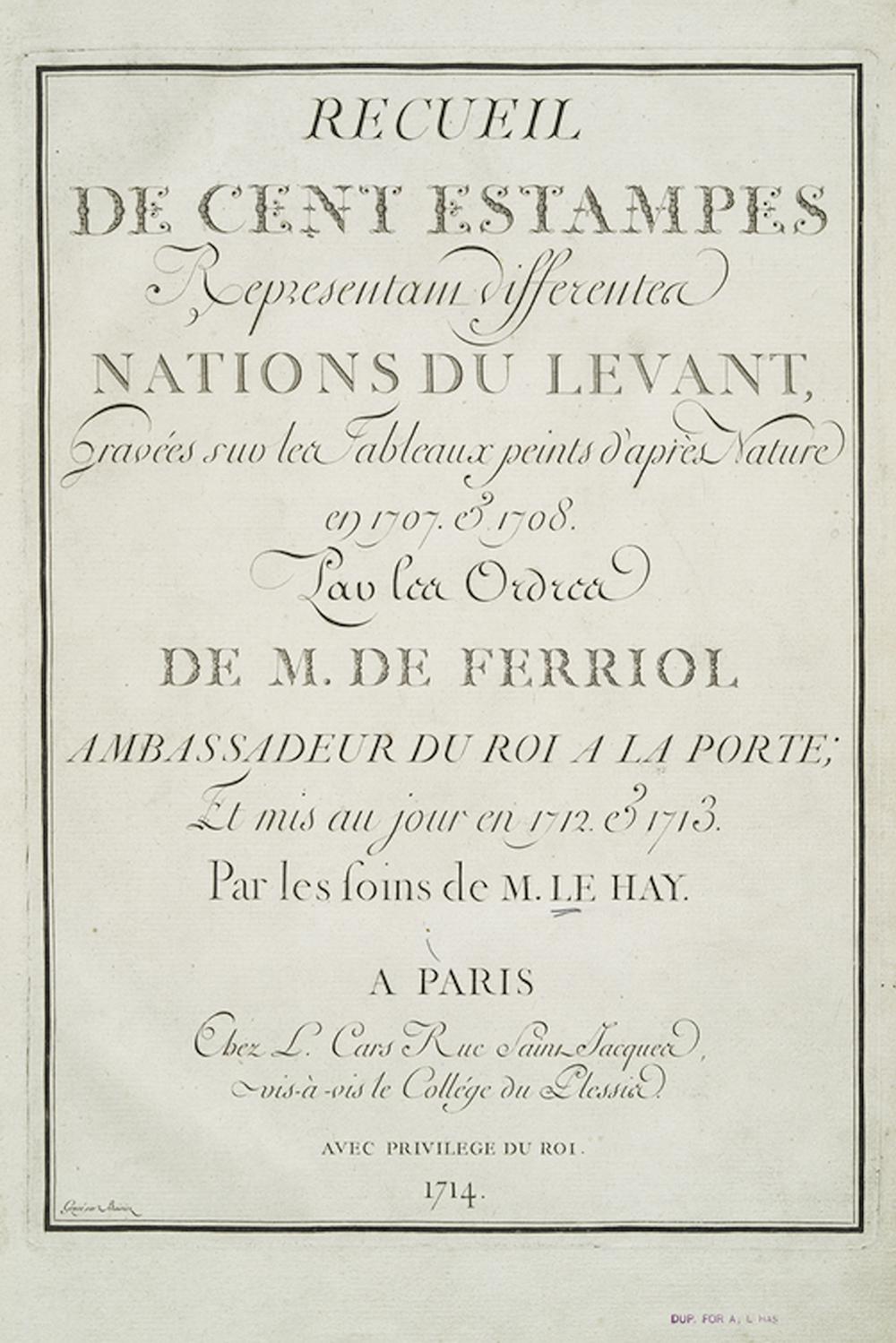

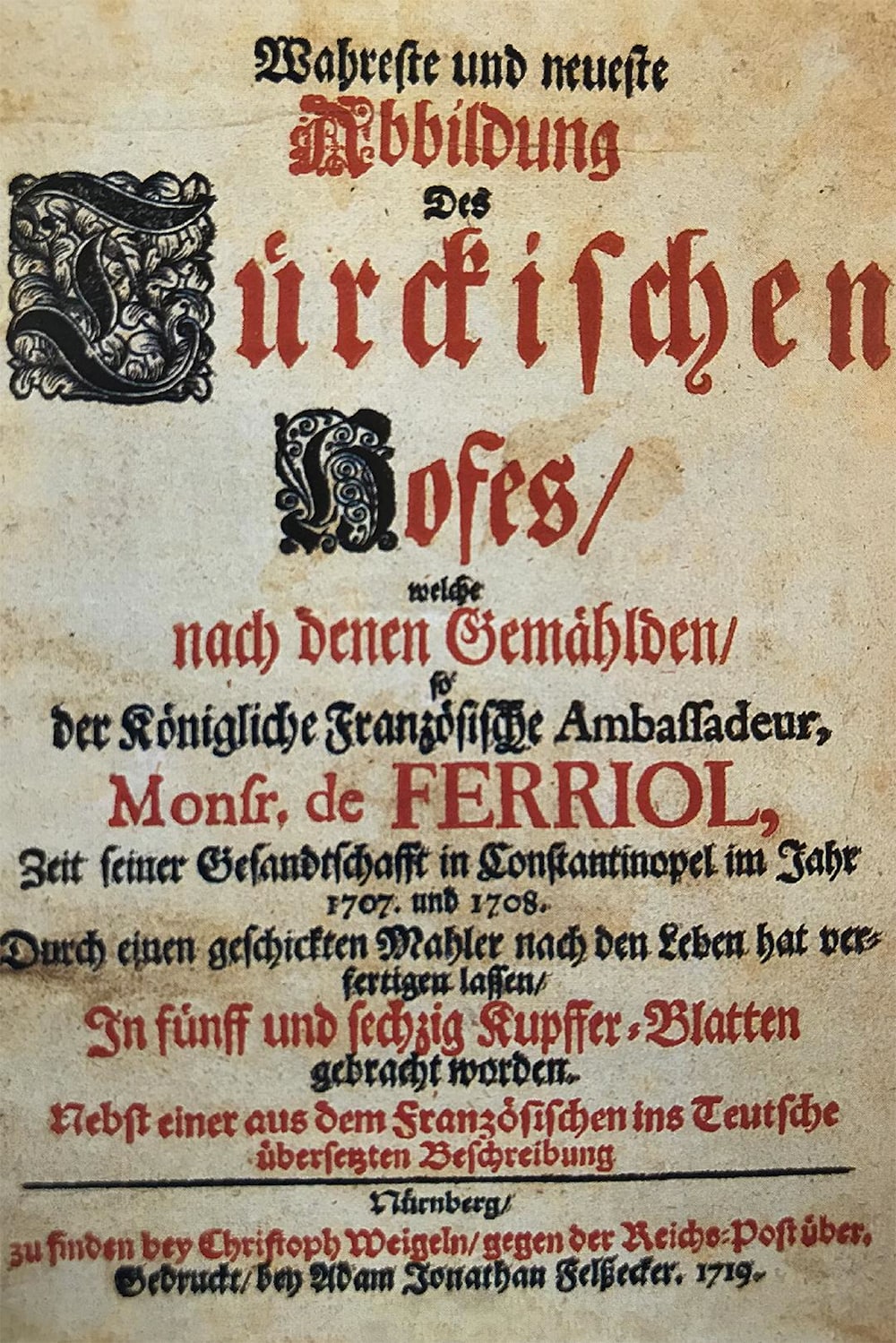

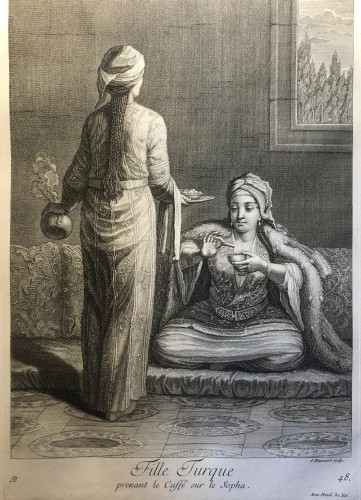

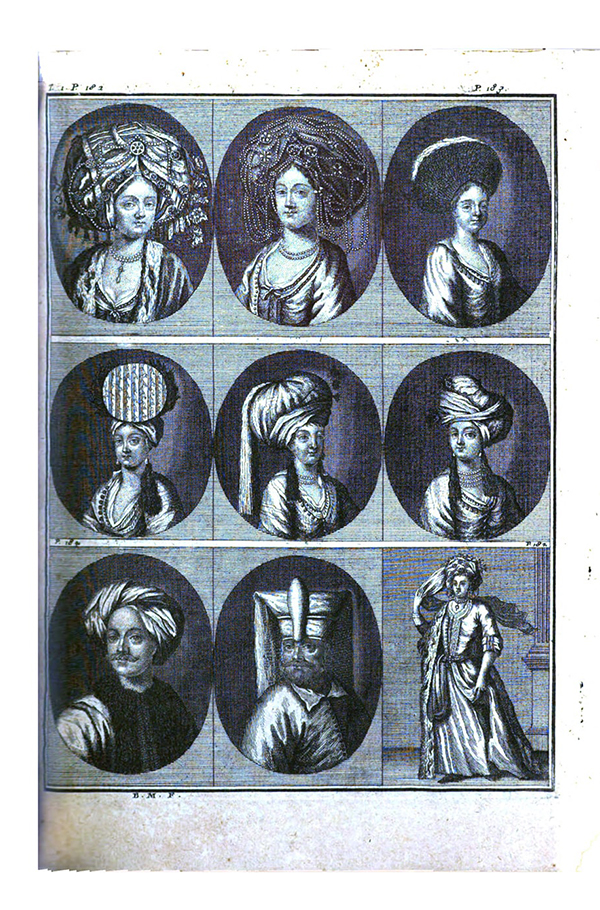

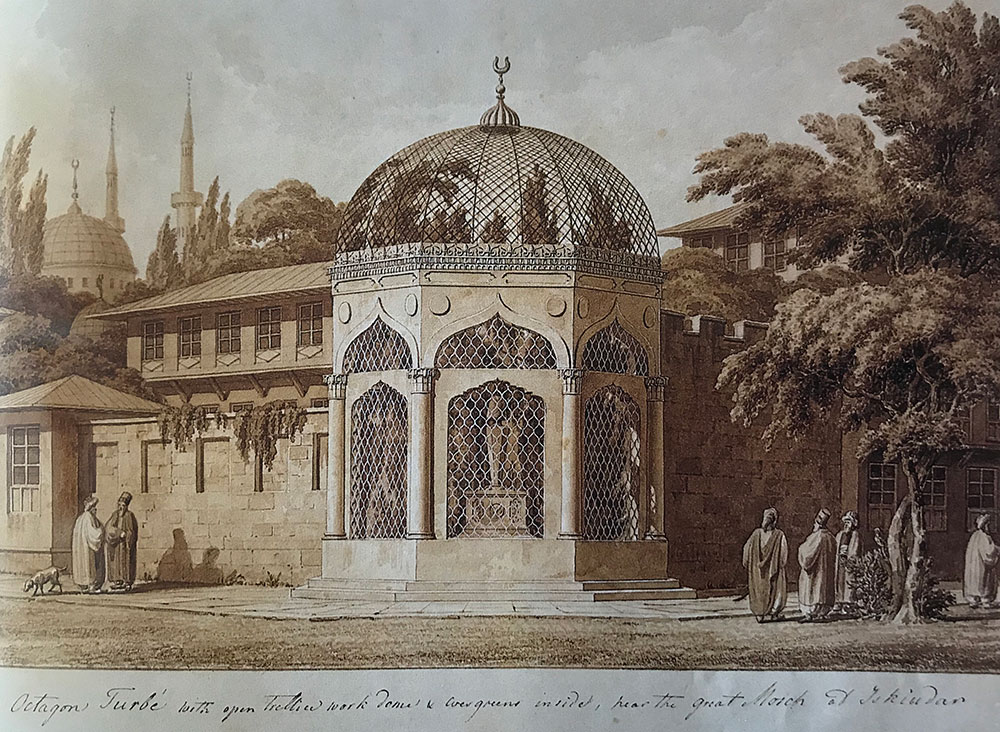

European artists had visited Istanbul and drawn its inhabitants at least since the days of Gentile Bellini (d. 1507), Nicolas de Nicolay (d. 1583), and Melchior Lorck (d. after 1583), but the artist perhaps most responsible for the popularity of Turquerie in the eighteenth century was the Flemish-French painter Jean Baptiste Vanmour (d. 1737). Having come to Istanbul in 1699 in the suite of the French ambassador Marquis Charles de Ferriol, Vanmour remained in Istanbul for almost four decades until his death in 1737, producing hundreds of images ranging from city views, parades, and ambassador’s audiences to portraits of Ottoman statesmen and ordinary people. In 1707, he was commissioned by his French patron, Ferriol, to produce a hundred images of different inhabitants of the city depicted in their official or ethnic costumes. His images of Sultan Ahmed III, various members of the Topkapı Palace, and inhabitants of the city (including Armenians, Albanians, and Europeans) were engraved and published in Paris. Entitled Recueil de cent estampes représentant différentes nations du Levant (1712–13), the volume was soon translated into various European languages and became highly influential among artists seeking first-hand sources on oriental costumes and furnishing. Vanmour received the title of peintre ordinaire du roi en Levant in 1725, but his artistic connections were not limited to France. In 1727, the Dutch ambassador Cornelis Calkoen commissioned Vanmour to paint the ambassador in the Reception Chamber of the Topkapı Palace. Indeed, Vanmour was one of the first European painters to have the honour of entering the Topkapı Palace, painting many other ambassadors’ audiences in the Reception Chamber.

Before railroads and steamships made travel to the Ottoman Empire affordable and accessible, the Orient appeared as a theme and influence in European culture mainly in the accounts of travellers. Vanmour’s portrait of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (d. 1762) in Ottoman garb, depicted with her son Edward and two other attendants, was painted in Istanbul between 1717 and 1718 when she accompanied her English ambassador husband. Lady Montagu’s regular letters home to her friends with details about her Istanbul life, and the Ottoman costumes she purchased in Istanbul and continued to wear once back in England helped popularize the fashion of Turquerie. The British upper classes gradually appropriated the oriental exotic as a way to distinguish themselves from those of lower status. British historian and anecdotist Joseph Spence, for instance, spoke with great admiration of John Montagu, fourth Earl of Sandwich, who extended his grand tour in the late 1730s to the Ottoman Empire: “A man that has been all over Greece, at Constantinople, Troy, the pyramids of Egypt, and the deserts of Arabia, talks and looks with a greater air than we little people can do that have only crawled about France and Italy”.

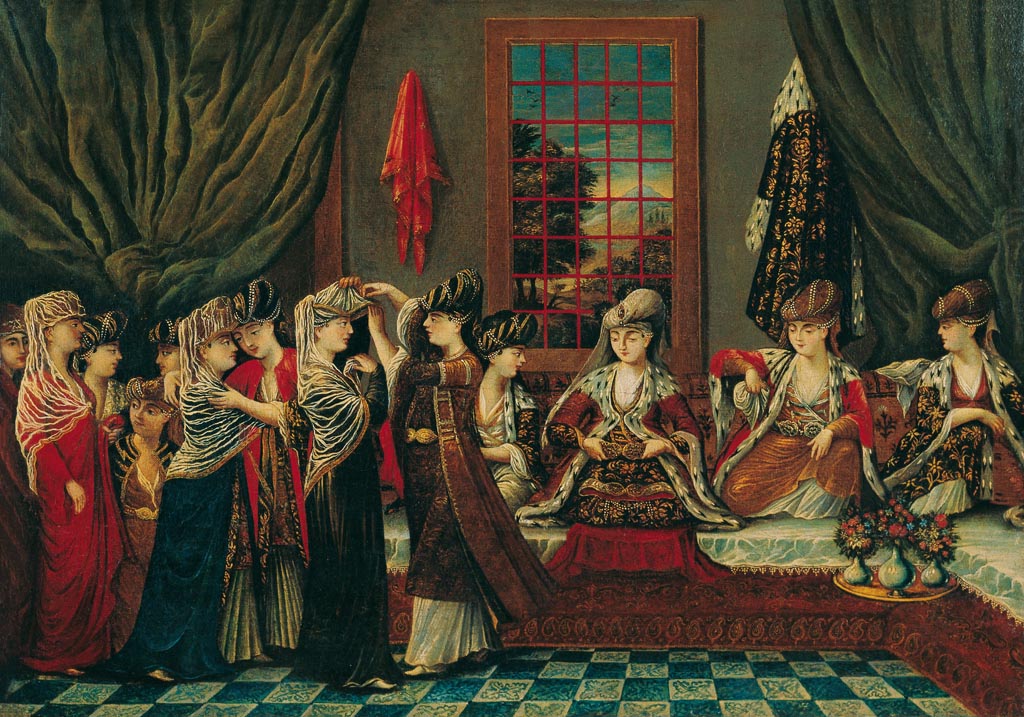

In contrast, the French upper classes, perhaps under the influence of Antoine Gallant’s wildly successful 1704 translation of the Thousand and One Nights, seem to have associated Ottoman culture with femininity, idleness, and pleasure. As a relatively novel product imported to Europe via Istanbul and Cairo, coffee became a key signifier of a sophisticated and wordly patterns of leisure and consumption, and features prominently in interior paintings of oriental women, such as Vanmour’s Turkish Girl Drinking Coffee on a Sofa and Women Drinking Coffee, as well as several anonymous contemporary images inspired by his work: The Day after the Wedding: the Feast of Trotters and Pleasure of Coffee. It is interesting to note that the exaggeratedly elaborate turban in the mid-eighteenth century Pleasure of Coffee seems to have been lifted from a more suspect source, Reizen van Cornelis de Bruyn (1698).

In particular, in portraits of Westerners dressed in oriental garb, luxurious splendour and a sexual subtext often become as much the subject as the sitter. The French ambassador to Istanbul, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, commissioned local French painter Antoine de Favray to paint his portrait (1766) and later that of his new wife Anne Testa (1768) in bright and luxuriant Ottoman costumes. The representations of the two figures seated on luxurious furs and cushions were in striking contrast to a courtier’s life at Versailles in the eighteenth century, which comprised long hours of standing; moreover, Anne is not depicted creaking uncomfortably in a corset, essential underwear for a contemporary courtly lady, but sitting at ease in a relatively loose dress. A popular genre was notable ladies being attended en sultane; for instance Mademoiselle de Clermont (d. 1741), painted seated bare-legged on sumptuous carpets at her bath side by Jean-Marc Nattier, or Madame de Pompadour (d. 1764), the chief mistress of Louis XV, painted being served coffee in her risqué “Turkish boudoir” by Charles-André van Loo. In both portraits, the French women are waited upon by other key signifiers of spending power in this period; black women or child servants; or, within the logic of the fantasy, slaves.

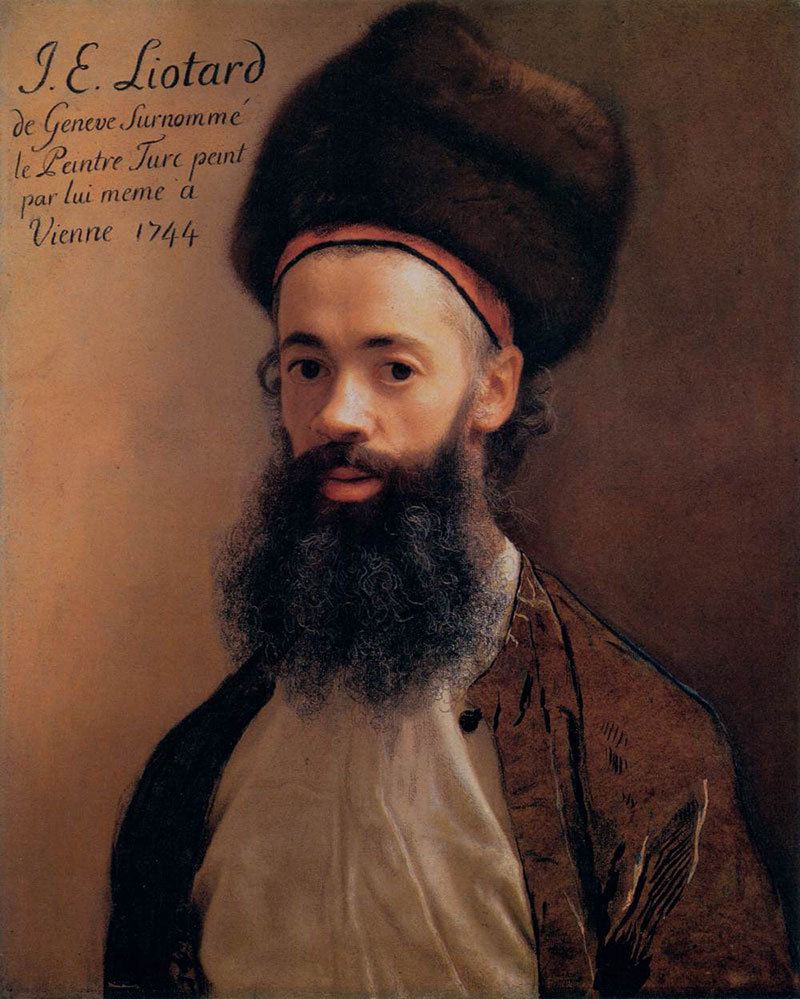

Not only aristocrats but also the enterprising bourgeoisie sought to rediscover themselves in the funhouse mirror of oriental fantasy. The Swiss painter Jean-Etienne Liotard (d. 1789), moved to Istanbul in 1738 and stayed there for five years, painting the various inhabitants of the city in their Ottoman attire. While there, he adopted what one of his customers, the English anthropologist Richard Pococke, called “Turkish habit,” including an almost waist-length beard. It should be noted that facial hair, most especially beards, had generally fallen out of fashion in this period in Europe, and the ruthless westerniser Peter the Great had even levied a tax in 1698 against those Russians who refused to shave them off. When Liotard relocated to Vienna, he produced an unusual self-portrait in oriental attire and sporting his magnificent whiskers and beard, featuring an outsize signature and the inscription “known as the Turkish painter” that loudly proclaimed his new hybrid identity. Likewise, between 1787 and 1795, the wealthy art collector and classical scholar Thomas Hope undertook an eight-year grand tour in Europe and the Orient and recorded his impressions in about 350 unsigned drawings (now at the Benaki Museum, Athens). In 1798, he posed in the Ottoman clothes that he had purchased in Athens for the respected English portraitist Sir William Beechey. The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1799, and soon copied by the prolific and successful enamel painter Henry Bone. One interesting detail here is Hope’s slender moustache with its pointed ends curled upwards, a style later adopted by Lord Byron in his Albanian costume portrait.

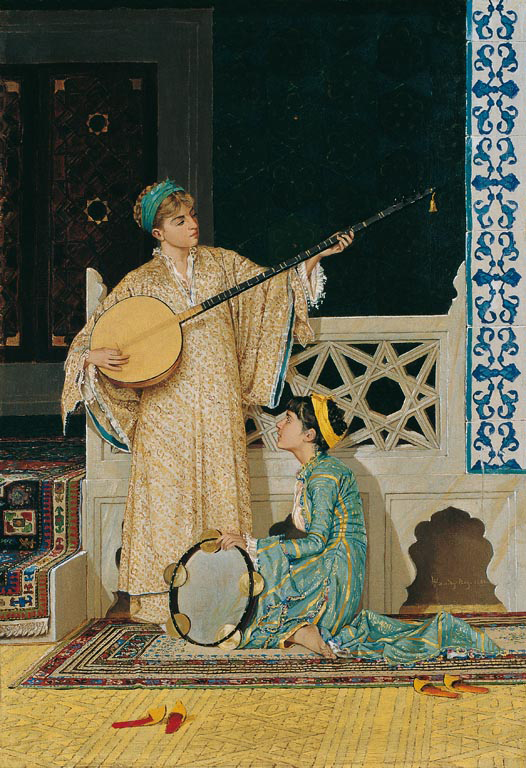

After the eighteenth century, however, the “dynamic and multi-actor phenomenon” of Turquerie became subsumed in nineteenth-century Orientalism, which would often presume the political and cultural inferiority of the Orient to rationalise and sustain Western dominance over it. This imperial imperative is clearly dominant in the Othering and often sexually-charged images of the East by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (d. 1867), Eugène Delacroix (d. 1863), and Jean-Léon Gérôme (d. 1904), although critics have sought to recover elements of serious cultural encounter and self-exploration in the works of painters like John Frederick Lewis (d. 1876) and the Ottoman orientalist painter Osman Hamdi Bey (d. 1910). Nevertheless, as Linda Nochlin put it, in all those works, the Oriental world appears as “a world without change, a world of timeless, atemporal customs and rituals, untouched by the historical processes.” (Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient”, The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society [1989], pp. 35–36.)

Looking back, it has become clear that such currents as Orientalism and Turquerie were not, as previously thought, unidirectional relations between the active West and the passive East, that the West had interlocutors in the East, indeed that Orientalism was sometimes confronted by Occidentalism. At the same time, a more objective and critical perspective on Turquerie reveals such problematical aspects as the “Othering” that lay behind superficial admiration, the impulse to reduce an entire nation to a handful of stereotypes, the drive to commodify and appropriate its culture, and the power to determine the way it would be represented without its consent. Establishing a monopoly and dominance over the Other’s representation (in the words of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, the application of “epistemic violence”) is never innocent; those who now praise Le Turc généreux may well, one day, turn around and curse “the barbaric Turk.” In short, it is necesary to take up the Turcophilia of eighteenth-century France together with former President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s assertion, a few centuries later, that “Turkey is not a European country.” (Le Monde, 9 November 2002)

* The authors would like to thank Yan Overfield Shaw for his suggestions.

Authors: Dr. Gizem Tongo and Irvin Cemil Schick

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)