21 April 2016

What will be the aim of the painting in the future? The same as that of poetry, music and philosophy. To give sensations that were previously unknown.

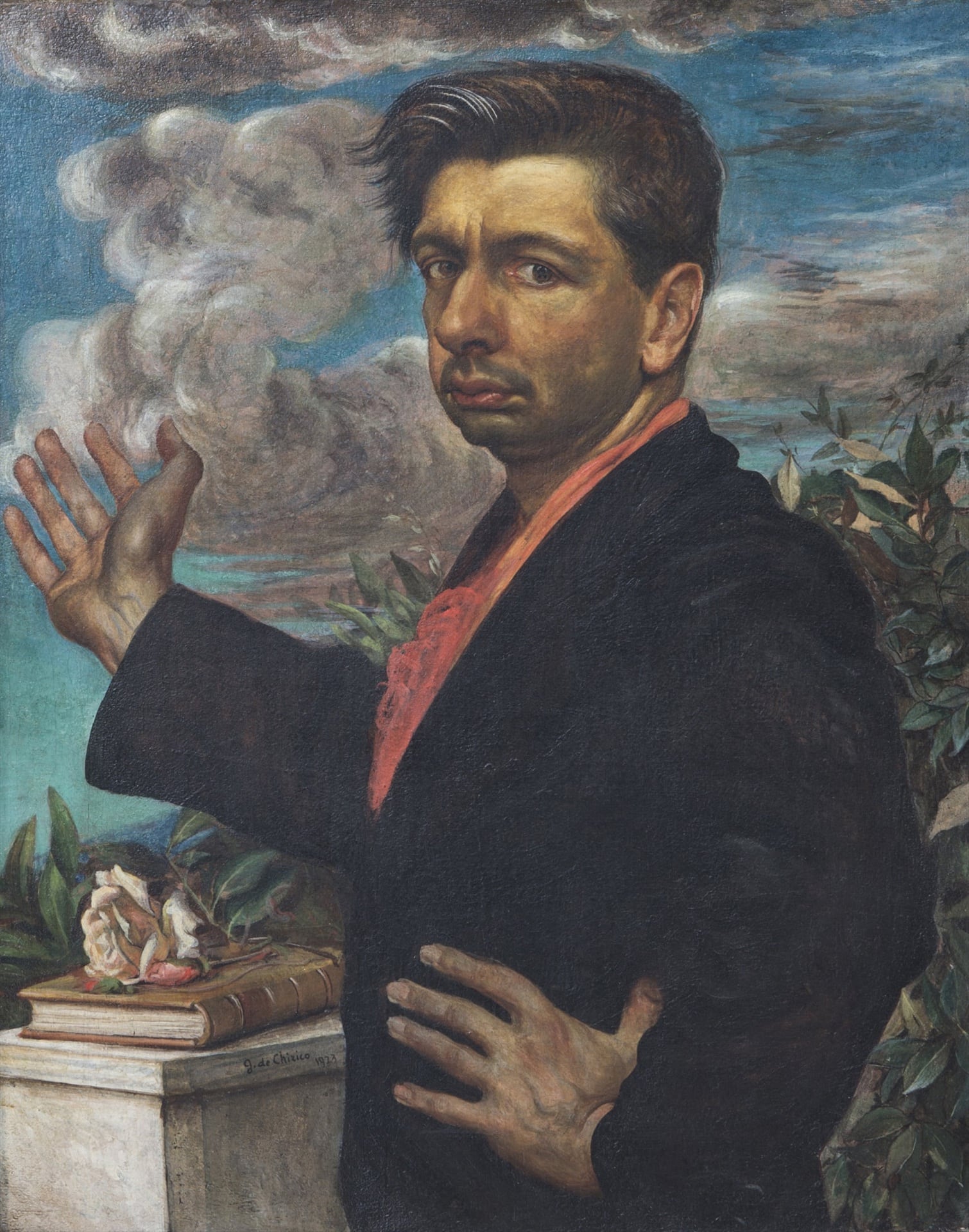

Self-portrait with a Rose, 1923,

Self-portrait with a Rose, 1923,

Tuval üzerine yağlıboya, 75 x 60 cm.

Private Collection

Pera Museum is proud to present an exhibition of Giorgio de Chirico, a pioneer of the metaphysical art movement and one of the most extraordinary artists of the 20th century.

We share Giorgio de Chirico’s “What Painting of the Future Could Be?” (Que pourrait etre la peinture de l’avenir) article, originally written in Frech in 1912!

What will be the aim of the painting in the future? The same as that of poetry, music and philosophy. To give sensations that were previously unknown. To strip art of every residue of routine, of rules, of tendency towards a subject, an aesthetic synthesis; to wholly suppress man as a point of reference, as means for expressing a symbol, a sensation or a thought: to free oneself once and for all of everything that continues to hold back sculpture: anthropomorphism. To see everything, man included, as a thing. It is the Nietzschean method. Applied to painting it could give extraordinary results. This is what I am trying to prove with my paintings.

When Nietzsche speaks of the pleasure he found in reading Stendhal, or in listening to the music from Carmen, one senses, if one uses a bit of psychology, what he meant by this: it is no longer a book, it is no longer a piece of music; it is something that gives a sensation; we weigh and judge this sensation, we compare it to others more commonly known and we choose it as we find it to be the newest.

A truly immortal work of art can only be born from revelation. It is perhaps Schopenhauer who best defined this and, one could even say, actually described such a moment when in his Parerga und Paralipomena he says: “In order to have extraordinary, original or even immortal ideas it suffices to isolate oneself completely from the world and things, for a few instances, so that the most ordinary objects and events appear to us as completely new and unknown, thus revealing their true essence”. Now, instead of the birth of original, extraordinary, immortal ideas, just imagine the birth of a work of art, a painting or a sculpture, in the mind of an artist and you will grasp the principal of revelation in painting.

In regard to all these questions, I will now explain how I had the revelation of a painting which I exhibited this year at the Salon d’Automne entitled: The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon.

On a clear autumn afternoon, I was sitting on a bench in the middle of Piazza Santa Croce in Florence. Indeed, it wasn’t the first time I had seen this square. I had just recovered from a long and painful intestinal illness and found myself in a morbid state of sensitivity. All of Nature surrounding me, even the marble of the buildings and the fountains, seemed to me to be convalescing also. In the centre of the square stands a statue of Dante cloaked in a long robe, hugging his oeuvre to his body, thoughtfully bowing his pensive laurel-crowned head toward the ground. The statue is of white marble, to which time has given a grey tinge that is very pleasing to the eye. The autumn sun, lukewarm and without love, lit the statue as well as the facade of the temple. I then had the strange impression that I was seeing everything for the first time. And the composition of my painting came to me and every time I look at it, I relive this moment once again. Still, the moment is for me an enigma, because it is inexplicable. And I also like to define the resulting work as an enigma.

Music cannot express the nec plus ultra of sensation. One never knows what music is about. Having heard any piece of music, everyone has the right to say, and can say, what does this mean? In a profound painting, on the contrary, this is impossible; one must fall silent when one has penetrated it in all its profundity. Then light and shade, lines and angles and all the mystery of its volume begin to speak.

The revelation of a work of art (painting or sculpture) can be born of a sudden, when one least expects it, and can also be stimulated by the sight of something. In the first instance it belongs to a class of rare and strange sensations, which I have observed in only on man: Nietzsche. Among the ancients, perhaps (I say perhaps because I sometimes have doubts) Phidias, in conceiving the plastic form of a Pallas Athena, and Raphael whilst painting the sky and the temple of his The Marriage of the Virgin, in Milan’s Brera Picture Gallery, had this sensation. When Nietzsche speaks of how his Zarathustra was conceived and says: ‘I was surprised by Zarathustra’, the participle ‘surprised’, holds within itself the whole enigma of sudden revelation.

When a revelation results from the sight of an arrangement of objects, then the work that appears in our minds is closely linked with the circumstance that has provoked its birth. It resembles what is seen, but in a very strange way, like the resemblance between two brothers, or rather between the image of someone we know seen in a dream and that person in reality; it is, and at the same time it is not, the same person; it is as if a slight and mysterious transfiguration of the features has taken place. I believe that, as the sight of someone in a dream is, from a certain points of view, proof of their metaphysical reality, the revelation of a work of art is, from these same points of view, the proof of the metaphysical reality of certain accidental occurrences that happen to us at times, of the way and disposition with which something presents itself to our view and provokes in us the imagine of a work of art; an image that awakens in our soul a sensation of surprise, often of meditation and always of the joy of creation.

Not: G. de Chirico, Que pourrait être la peinture de l’avenir (Paris: Manoscritti Paulhan, 1912); partial English translation in J. Thrall Soby, Giorgio de Chirico (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1955); published in G. de Chirico, Il meccanismo del pensiero, edited by M. Fagiolo dell’Arco (Turin: Einaudi, 1985); now in Scritti/1 (1911-1945). Romanzi e scritti critici e teorici, edited by A. Cortellessa, editorial director A. Bonito Oliva (Milan: Bompiani, 2008), 649-652.

Highlighting his various periods with examples from his earliest works to last ones, Giorgio de Chirico: The Enigma of the World exhibition took place at the Pera Museum between 24 February - 08 May 2016.

Pera Museum Blog is launching a new series of creepy stories in collaboration with Turkey’s Fantasy and Science Fiction Arts Association (FABISAD). The Association’s member writers are presenting newly commissioned short horror stories inspired by the artworks of Mario Prassinos as part of the Museum’s In Pursuit of an Artist: Istanbul-Paris-Istanbul exhibition. The third story is by Murat Başekim! The stories will be published online throughout the exhibition. Stay tuned!

Pera Museum, in collaboration with Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (İKSV), is one of the main venues for this year’s 15th Istanbul Biennial from 16 September to 12 November 2017. Through the biennial, we will be sharing detailed information about the artists and the artworks.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)