28 April 2023

While Paula Rego belatedly was recognised as one of the leading feminist pioneers of her age, little has been written about her exploration of fluid sexuality. Indeed the current of sado-masochism in her drawings and paintings, has tended to encourage an understanding as a classic clash between the patriarchy and exploited women. Her first museum exhibitions in Turkey and Germany show that she had a far more fluid appreciation of gender and identity than which she has been credited.

In Turkish Bath, Rego literally turns the male gaze on its head. In 1960 she took a canvas on which her husband, Victor Willing, had two years earlier painted her. She is depicted as a naked, demure, acquiescent woman. She turned the canvas upside down and used the back of the canvas to make a collage that mocked the male gaze on the other side. She went further: she put together a kaleidoscope of images made by Occidental men of ‘exotic’ Eastern women. She even took the title from Ingres and other 19 th century men who were fascinated by the harem and other ‘forbidden glimpses’ of women baring their normally much-guarded bodies. There is not one single focal point in Rego’s picture, but one of the main areas to catch the eye is an advertisement for Le Pilules Orientales, which were meant to enhance your bust. It seems to have worked on the man above the advert. There is an echo of Duchamp with an added moustache and then critically a crudely drawn pair of bosoms. This painting was made 18 years before the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism. She was determined even then to free us from the limited ideas about gender and race.

In the early 80s Rego’s explodes with a new vitality. It is as if life itself is pouring out onto her studio floor. She worked on the floor, kneeling above the paper. The urge to create seemed so great, the need to get images out so pressing. It was sketching on a large scale. The creatures she drew were not finished polished human beings, but animals and other partly-evolved phantoms. She painted a series on Operas and one can almost feel the urgent beat of Carmen, Traviata and Rigoletto. That sense, present to some degree in all art, was that she was re-making the world, and in the process actually revelling in the chaos out of which our semblance of order comes.

Paradise, 1985, has a direct reference to a creation story even its title, but in it the artists questions our idea of belonging to a place and our dreams of the Garden of Eden, our eternal restlessness, our permanent discontent. Her first depiction of a firmly grounded ‘man’ stands just off centre of the picture. They seem to be content with themself. He wears a skirt and a flower in his long hair. His/her/their gender is not an issue. The person is at ease with the lush nature around them. Indeed they seem to have the devil, represented by the serpent, who wishes to enter and disrupt Eden, grasped tightly in their hand. A little insect, which is at risk of being a snake snack, hovers in front of its fang, teasing it. In Rego’s version, it is the missionary who sullies Eden. She is there, dolled up inappropriately in a dress, cosmetics and a silly hat, thinking she can save paradise from itself. She was all to successful. In looking to convert and civilise Paradise, little ‘Miss Perfect’ corrupts the figure who until that point appears to have been more than content in their undefined, unlimited sexuality.

The Maids, 1987, is based on Jean Genet’s sado-masochistic ‘masterpiece’ of the same title. I insert the inverted commas as there are no masters in Genet’s play. The only concession to a male presence in Rego’s version is a rather pathetic stuffed boar in the bottom right-hand corner. It is all about a power struggle but it doesn’t involve men. It is between the mistress-of-the-house and the maids. Rego, in her pictures, gives power to the oppressed. The maids have countless opportunities to slit their mistresses’ throat. They act and re- act it out. One could make an endless production of the play in that play-acting is the play, the role play, not the potential murder.

The Maids is set in the memory of Paula’s mother’s bedroom in which the young Paula grew up. The mistress is largely based on Dona Violeta, the bully of a tutor that used to come to give Paula personal and much hated lessons. The thought of revenge may have helped the young artist survive the blows, both physical and mental, inflicted by the classroom dictator. Certainly she gets it when she paints the ugly madame. What does this say about fluid sexuality? As always the artist did not give too much away. She made the most of ambiguity. Yet in the role play she looks as if she is pushing the vile Violeta into a traditonally male position. She has a moustache. She is playing with traditional roles.

Much of Rego’s work attacked the binary way in which the world has been controlled under the Patriarchy. Her severest, and at the same time gloriously liberating, examination of her own behaviour and feelings is the Dog Woman series, which she started making some five years after her husband died after 22 years of suffering from Multiple Sclerosis. Intriguingly she had used dogs before in her pictures and most recently showing her husband as an incapacitated pet needing care. There was no escaping his dependence on his carers. Yet the 1994 Dog Women are definitely about her. Whereas The Maids, made while Victor Willing was still alive, has strong sexual tension between the women, and the male presence is reduced to a toy boar, the Dog Women are invariably about single individual women on their own. The titles (Good Dog, Bad Dog, Baying and Sit!) lay the parameters. The question is not just how one set of people can treat the others as dogs, it is why the other set let it happen. And of course even in single figure it is more complicated than that. Power play, role play, submission, domination, they can all take place in one single mind and heart. The dogs may be servile yet that does not preclude them from growling, snarling, howling or looking serene. So the current Pera exhibition concludes with Sit!, a painting that shows a person obediently sitting on their hands, but the look in their eye is as free as the birds – there is certainly more than one narrow identity in there.

Cross-dressing, if that is what it is, recurs in Rego’s work: In the Company of Women, 1997, Olga, 2003 and Paradise, 1985. Yet the easy shifts in sexuality never undermined the strong sense of identity Rego gives in her work. She may have been shy in person at times, but in her work she is confident. This comes over most emphatically in the magnificent Artist in Her Studio, 1997. This can be interpreted as a mockery of the male fantasy of the Bohemian male artist in his studio, surrounded by his trophies, but that is but part of the story. The pose of the artist with feet wide apart and puffing at a pipe does ape a male stereotype, but it also has echoes of George Sands. The characters in the picture, apart from the yokel from a bygone age and prejudice and a well-dressed banjo-playing rat, are all very diverse women. The underlying message is that she may not be in total control of what is happening around but she will go on drawing and painting as she has done since she was the child in the right hand bottom corner. She is not a collector of objects like those accumulating cabinets of curiosities in the past.

Alistair Hicks

This article was published on RAW+blog on 17.02.2023.

Although traditionally used as a medium for functional or decorative objects, ceramic has become a medium that is increasingly used by contemporary. Here is the work of some important contemporary ceramic artists from around the world!

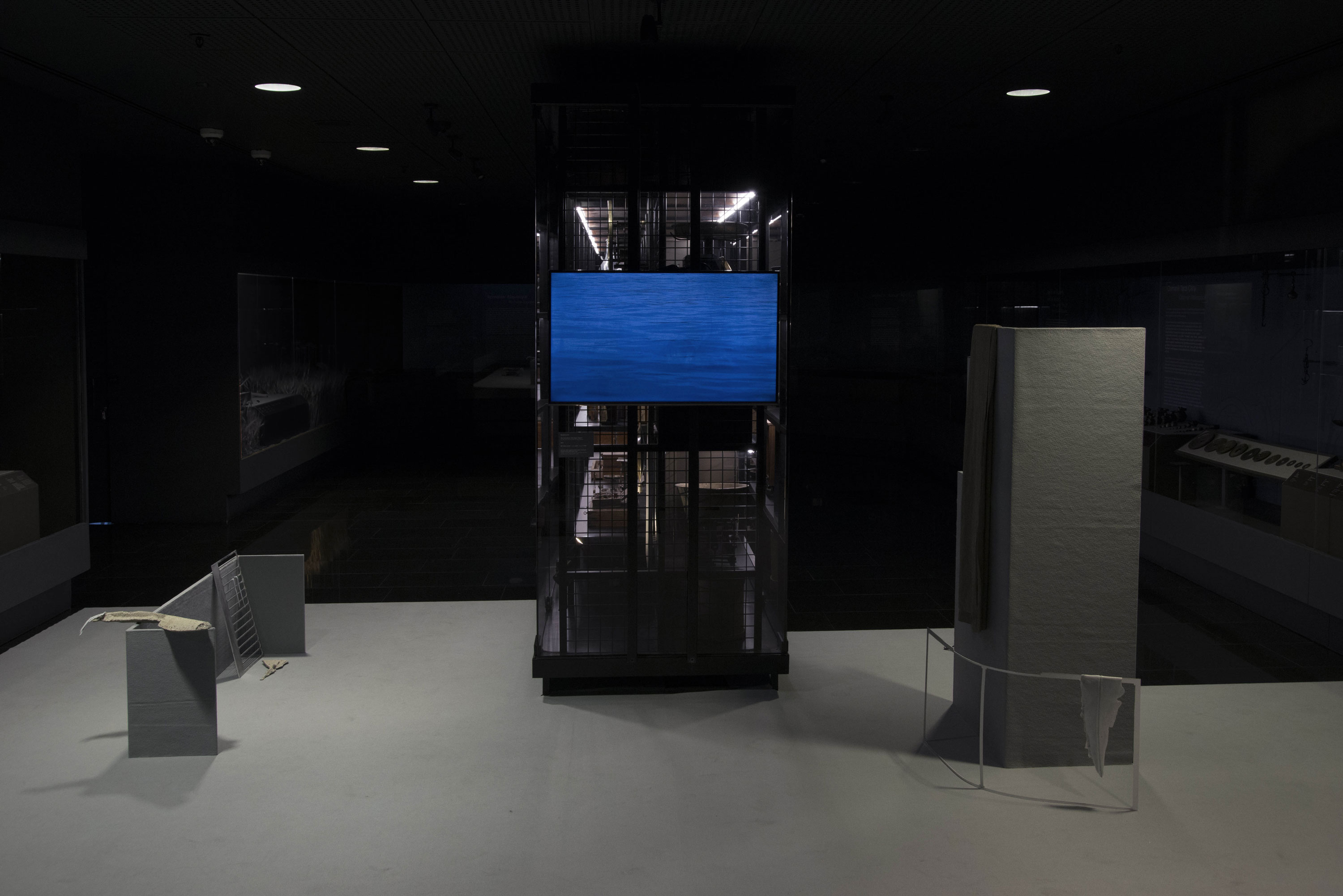

Inspired by its Anatolian Weights and Measures Collection, Pera Museum presents a contemporary video installation titled For All the Time, for All the Sad Stones at the gallery that hosts the Collection. The installation by the artist Nicola Lorini takes its starting point from recent events, in particular the calculation of the hypothetical mass of the Internet and the weight lost by the model of the kilogram and its consequent redefinition, and traces a non-linear voyage through the Collection.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)