24 June 2025

Ulya Soley

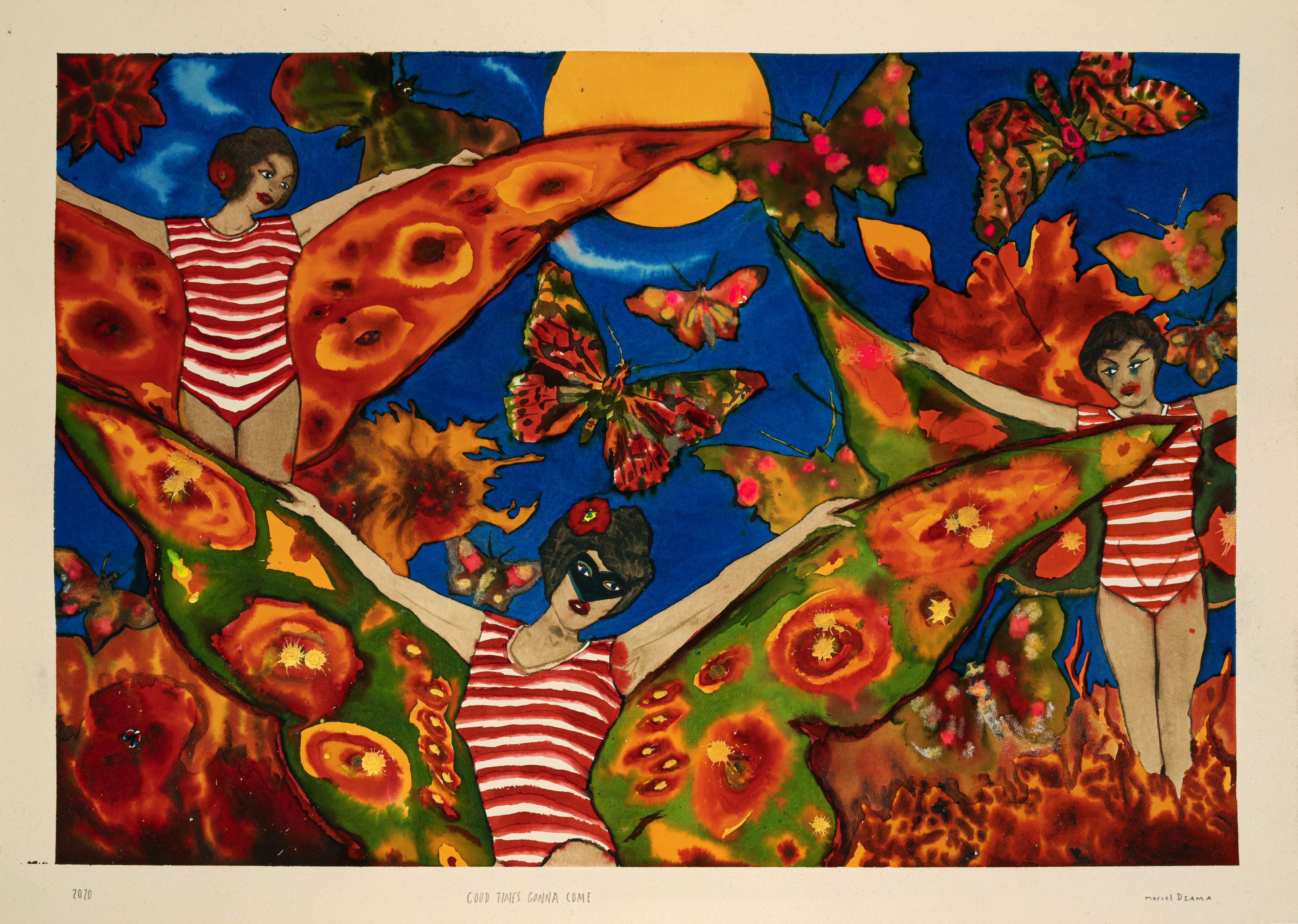

We meet at Marcel Dzama’s studio in Brooklyn on the occasion of his solo exhibition Dancing with the Moon at Pera Museum. On this freezing day in January, he welcomes us with a warm smile, and for a few hours, we step into his world filled with surreal characters, music, dance, politics, and play. Our conversation takes us through retro films, the characters that appear in his drawings, snowy landscapes, his collaborators, ballet and theater scenes, and family relationships, all the way to his recent focus on the Lorca project and what awaits us in the exhibition. As we journey from his early artistic productions in his hometown of Winnipeg to the present, our conversation is occasionally accompanied by Marcel playing a Leonard Cohen song on his guitar or the soundtrack of his film playing in the background.

Ulya Soley: It is fascinating to see where you produce your works and share this studio space with you. Can we start by talking about your routines in the studio? How does a typical day look to you?

Marcel Dzama: I kind of keep a reverse schedule, I’m on vampire hours, so I usually work at night time. I’m usually up in the morning with my son, I take him to school and then when he’s at school, I sleep, and then when he comes back, I wake up. Then I usually start working when he goes to sleep, so I’m with him during the day from after school. On the weekends, it gets a bit messy because I try to be normal but it messes up my schedule a little bit there. I’ve been working mostly at home just because of the cold weather and my bad hours, but I do work in the studio quite a bit. I have a studio in my home as well.

US: We are in this very crowded, full space, but it is very tidy at the same time. How does it feel to produce in this environment?

MD: The house is also full (laughs). A lot of books, a lot of masks, costumes. It’s an organized chaos, I guess. I know where things are, but I don’t think a lot of other people would know. Or at least I fool myself into thinking that I know where things are.

“I’ve been kind of obsessed with the moon... It really had the surreal negative feeling on the world stage and the environment.”

US: You often work at night and you have a tight relationship with night time, the exhibition will also feature this keen interest. The cover image of this book is another night scene titled Good night New York. Can you explain what fascinates you about night?

MD: I have one foot in the subconscious and the other in reality, so at night it’s that kind of feeling, and there’s no interruptions. You can’t even order food, things are closed. I usually start working around 9-10 at night until 6 in the morning, and then I get my son’s breakfast ready and then he goes off to school. I used to drive him, but now he takes the bus. So the work on the cover is the one with Raymond [Pettibon], with the Statue of Liberty in the water. Raymond had drawn the Statue of Liberty and I had added my son on the shoulder of the Statue and put it flooded instead of just standing there, and Raymond had drawn a bird at the top and I added the moon. I’ve been kind of obsessed with the moon. I think we did it when Trump got in office for the second time. It really had the surreal negative feeling on world stage and the environment. It’s liberty and the environment taking over or losing.

US: I would like to continue with your personal story a little. You were born in Winnipeg, Canada and then you moved to New York after art school. Can you describe your surroundings growing up? What was it like to spend your childhood and teens in Manitoba?

“A lot of that isolation in winter made me kind of invent my own world in drawing. And also prepared me for the pandemic.”

MD: Growing up in Winnipeg was very cold and isolated. In the winters I was drawn to children’s books. I still played with kids outside for the minimum amount of time that you could play because you would freeze very quickly, it was -40 for weeks at a time. So I would draw constantly. A lot of that isolation in winter made me kind of invent my own world in drawing. And also prepared me for the pandemic, I was totally fine with it. Staying in for months at a time. And then also my grandfather and I used to go to this farm a lot. We would go to the garbage dump and see bears and other animals. I used to draw a lot of bears in the early drawings. I guess they still come up. That’s where I’ve seen the real wildlife. There were cows, bulls, pigs and chickens. He had a forest which was invaded by fungus or bugs, the trees were all dead. And there was this really creepy forest where I think that a lot of the tree creatures kind of came from there. The fact that Winnipeg peaked in the 1920s also influenced my style, I do have a bit of a retro style—20s to 30s but looking towards the future.

US: You create environments that blur the boundaries of time periods—it could be 20s or 2025. How do you see your relationship with time?

MD: When you are in Winnipeg, you do feel like you are in the past but you are also in the present and there is that part of future happening. So there is that ‘all times exist all together’, there is a past, present and future all existing at once. I guess it is supposed to be true as well but it doesn’t feel like it when you are moving quickly. Not as much in New York, it feels much more fast moving forward. In Winnipeg the pace is a lot more slower. So maybe there is more of a past and present existing less than the future. And the fact that it peaked so long ago, the population usually is going down. Young people usually move to bigger places like Toronto or Montreal.

“In art school everyone was talking about how the future was going to be all about computers, how art was going to be about computers as well and that we needed to learn as much as we can about them. Our movement was against all of that, we were bringing it back to just pencil and paper.”

US How was the art school in Winnipeg? I guess that’s when you started doing collaborative work as well? Can you talk about your artistic group?

MD: In Winnipeg, I was lucky enough to have my uncle Neal Farber, who is a year younger than me. My mother had me when she was 18, my grandmother had him when she was 39, so were more like brothers. I used to live with them in the summer, and when we were teenagers, he lived with us in the city. And then we went to university together, and we collaborated a lot in bands and short films. I have dyslexia, so he used to write a lot of papers for me. I would give the ideas and he would do the writing. He did most of the work and helped me cheat through the university. And then we started a group called the Royal Art Lodge in our last year of school with my little sister Hollie Dzama, who is 10 years younger than me. Michael Dumontier was in my class and Jon Pylypchuk too. We were in a lot of bands and our bands started to mix together. Our main format was drawing mostly. Right at that time in art school everyone was talking about how the future was going to be all about computers, how art was going to be about computers as well and that we needed to learn as much as we can about them. Our movement was against all of that, we were bringing it back to just pencil and paper. We were using our colors and that was about it. At least that’s how I felt. Some of them were able to do computer things but I’m pretty computer illiterate. We used to make a lot of videos and Neal would edit them on the computer. I was more of an analogue person, VHS to VHS.

US: Collaboration is an important aspect of your practice. In the exhibition, we will see some works in collaboration with your friend Raymond Pettibon. Can you talk a bit about your relationship with him? What is your methodology when working on a piece together?

MD: The first time we met we were at a David Zwirner dinner. We were both kind of socially awkward, and we both started drawing on napkins. We did all these drawings on napkins and table. People started giving us makeup and stuff because we ran out of pencils. Lucas Zwirner noticed that we did those drawings and at some point, he asked us if we would do a zine together. At first, we were going to do an exquisite corpse, you know the drawings where you fold it you don’t see what the other person’s drawing. But we found it more fun actually seeing what each of us was doing. And he gave me a big box full of drawings and I just started adding to them. Those turned out good, and that zine led to a show. Most of the strongest work was done three days before the show. We put a paper on the wall and started painting, it was really interesting because there was no real plan or even communication. We were just almost subconsciously working together. He was probably the first contemporary artist that I knew because of all the punk band covers that he’s done. I don’t know if I knew his name back then but I knew his artwork. My first show was in Santa Monica in LA and David Zwirner saw my work there because he was buying all Raymond Pettibon drawings off this gallery. So if it wasn’t for Raymond Pettibon, I’m not sure if I would be in the gallery that I am in. Also, he opened up drawing in such a strong way in contemporary art that if he hadn’t done it, I don’t know if I would get through that door either. He put his foot through the door and hold it for me to get in too. I always had that in my mind and I’ve always been a fan of his because of that and because of his talent. Also, our sons are the same age and they’ve become friends.

US: You also draw with your son and feature him in your video works. How do you usually collaborate with him?

MD: Especially during the pandemic I got to collaborate with him a lot, he was my main collaborator. We made a lot of films together. He would write films as well. I haven’t shown them because he has his face in them. He’s 12 now but back then he was quite younger. We make a lot of music now together. He likes singing and playing music, he plays saxophone and kind of plays guitar if I put effect pedals on it. He wants to be an artist but we don’t want to pressure him into that. He really wants to be a film-maker, he is kind of allover things, which is good. I think at that age you shouldn’t make a decision. When we draw together, I would draw and he would draw at the same time. So we don’t actually collaborate, we influence each other.

US: Apart from your drawings, you’re showing four video works in the upcoming exhibition. How do you feel about drawing versus working in film? How did you start making videos?

MD: I was doing videos before art school. I was actually making little short puppet films with my sister, that’s how it started. My parents bought me this Fisher Price camera, that was invented in the 80s, recorded on cassette tapes. It looked like old film, and I think maybe that’s the reason I got into it. My first films were with a film class in university. We actually worked with 16 mm. This old rushing camera Bolex, and the main actors were my father and my sister. I made masks for them out of papier-mâché because they would laugh when I was filming. A lot of the masks came out of that. I think I would use them otherwise but that was definitely the start of it. I could have any actor even if they couldn’t act if they had a costume on.

“I feel like Winnipeg in the winter is basically a blank canvas. Being on the prairie, it just goes on forever. The horizon and the skyline just meet together especially when you are out in the farm area, there are these wheat fields that are just empty full of snow.”

US: Dance and music are usually the key elements of your videos. The rhythmic elements of the videos are highlighted by the performers, and through repetitive move- ments and patterns you build worlds.

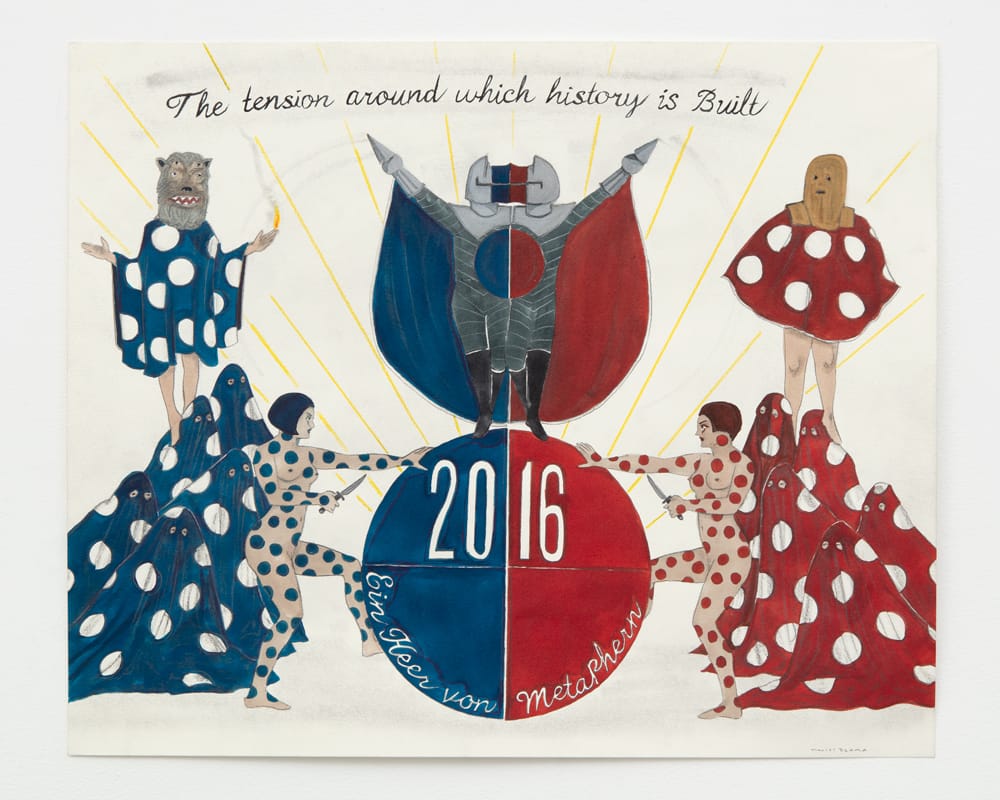

MD: When I moved to New York I really got into ballet. When I lived in Winnipeg the drawings were very simple. There was a blank background, I don’t know if this was conscious or subconscious but the background was all white. I feel like Winnipeg in the winter is basically a blank canvas. Being on the prairie, it just goes on forever. The horizon and the skyline just meet together especially when you are out in the farm area, there are these wheat fields that are just empty full of snow. The drawings when I lived in Winnipeg had these two or three characters doing some surreal kind of event. And then when I moved to New York, they became very dense and cluttered. To put order to chaos of these characters, I started putting them in ballet positions. I found these old ballet magazines from the 1960s and 70s. So I started putting the characters in these dance positions. That’s where I found out about Oskar Schlemmer, he is this Bauhaus artist that I got obsessed with. I started slowly making those drawings into a stage. I usually had a curtain on the side, and that’s where the musical element came in as well.

I was lucky enough to meet a choreographer; Justin Peck saw my show in David Zwirner in 2014, we ended up working together on the New York City Ballet. And Bryce Dessner, this musician from this band called the National. Both of them saw that show and gotten into contact with me. Then I did the ballet and I kind of burnt out after that. I did all the costumes, the stage, the backdrops, the curtains, and then also the promenade space, I did an art show there. I made these giant merry go rounds, made out of recycled tin in Guadalajara, Mexico during a yearlong residency. I started making ceramics and these kinds of sculptures there.

To read the our entire interview with Marcel Dzama, you may want to browse the catalogue. Click for more information about the catalogue.

Canadian artist Marcel Dzama shares five albums he listened to most frequently while preparing his exhibition Dancing with the Moon at Pera Museum. Spanning from post-punk depths to subtle folk tones, this list offers a glimpse into the sounds that shape his visual world.

Our institutions have been stuck on linear Neo-Platonic tracks for 24 centuries. These antiquated processes of deduction have lost their authority. Just like art it has fallen off its pedestal. Legal, educational and constitutional systems rigidly subscribe to these; they are 100% text based.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)